Lilly Gibson-Dougall | Cyber Security Fellow

Imagine if the late Carrie Fisher could have acted in the Star Wars film Rogue One, or if you could talk to an artist about their work even after they passed away. Sounds insane, right? But both of these were actually possible thanks to the emerging technology of deepfakes. An English hobbyist used neural networks to edit early career footage of Carrie Fisher into Rogue One, and the Dali Museum in Florida created an exhibition where deepfake technology was used so that visitors could interact with a deceased artist. But what really are deepfakes? And with art and technology evolving alongside each other in this area in such interesting ways, why are deepfakes so controversial?

Put simply, a deepfake is a type of forgery created by a neural network that analyses video footage until it can overlay the “skin” of one human face onto the movements of another algorithmically. There are also shallowfakes, which are videos shown out of context or doctored by simple editing tools. Finally, audio files can be cloned as well, with a CEO of a UK-based subsidiary company being defrauded last year by a group who mimicked the voice of the parent company’s chief executive over the phone. While deepfake technology is continuing to evolve, it is still often possible to determine when a deepfake is produced. However, this is changing as the technology becomes more readily available, cheaper, and easier for amateurs to use.

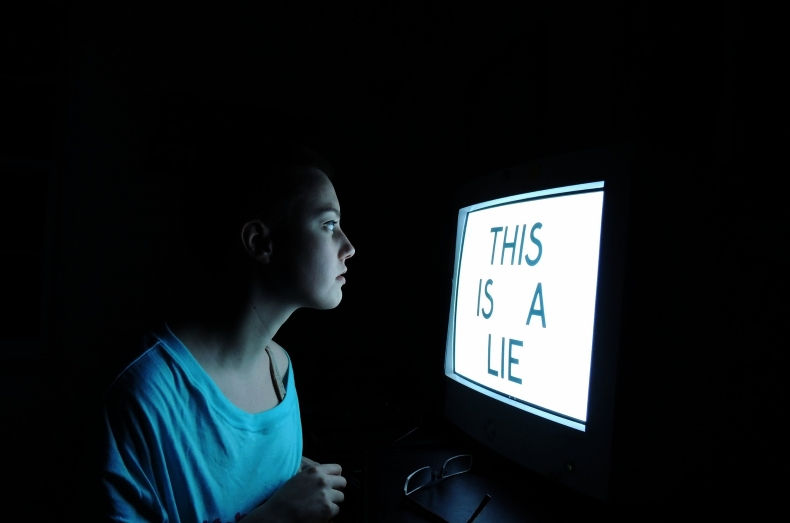

In terms of politics, this rapid expansion represents a dangerous development. During the 2016 U.S. Presidential election we saw a massive rise in ‘fake news’, with some research suggesting that 38 million shares of fake news stories on Facebook and other social media sites could have translated to 760 million total views. Adding deepfakes into this complicated social media setting could have a significant impact on the political system and the running of elections. We have already seen instances of deepfakes being used to interfere in politics, with a Belgium political party creating a deepfake of the U.S. President Donald Trump discussing his withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement. House speaker Nancy Pelosi has been the target of several shallowfake attacks, with one being slowed to slur her speech. There have also been claims that deepfakes may have contributed to discrediting the Malaysian economic affairs minister, and in escalating a coup in Gabon.

More concerning perhaps will be the ability of some to contest reality itself in a world where deepfakes become prevalent. If the technology to obscure reality exists, then those in the public eye can have more plausible deniability surrounding their actions. Prince Andrew and his allies have suggested that a photo taken with his arms around the waist of one of Jeffrey Epstein’s alleged victims is a fake. If the legitimacy of video, photo or audio evidence becomes difficult to confirm, then the potential for powerful figures to use this to their advantage becomes a very real threat.

More than that, the very trust in this type of material may also be diminished, increasing the likelihood that we will become more suspicious of and perhaps less influenced by photo and video media. This will not only have impacts on our judicial system with difficulties in proving the authenticity of such material, but also on our political system if people decide to disengage from political discussion and cement existing partisan bubbles.

While it’s easy to dismiss ‘fake news’ and those who are ‘fooled’ by it, it is symptomatic of a much larger problem within our society. It is a form of trolling, preying on societal discord and inequality, as a method of trying to force political outcomes and discrediting experts. By blaming those who are fooled, which is easier to be than we might think, we risk alienating sections of the population, and draw away from those who are perpetrating and profiting off this misinformation. Instead, we need to place the burden upon our media networks, social media companies and politicians who have certain duties to encourage political literacy, truth-telling, and critical thinking skills. Those who have the power and capabilities need to be at the forefront of this fight against misinformation and commit to upholding political stability.

Once again, we see the clash between the potential of technology and its impact upon society. The innovation and possibility deepfakes offer in the world of art, technology and filmmaking are truly phenomenal. Yet we need to be aware of the dangers deepfakes pose, and balance these two aspects against each other as best as we can.

Lilly Gibson-Dougall is the Cyber Security Fellow for Young Australians in International Affairs.

Kommentare